| Home Page | Overview | Site Map | Index | Appendix | Illustration | Preface | Contact | Update | FAQ |

|

|

As shown in Figure 07-11a, the giant outer planets consist mostly of hydrogen and helium gas and liquid, which surrounds a core of iron and rock and possibly a smaller amount of methane, carbondioxide and water ices. Jupiter is the largest planet, closely followed by Saturn. Uranus and Neptune are in comparison much smaller, although still significantly larger than any of the terrestrial planets. Jupiter is a "failed star" - it would have become a star igniting nuclear fusion at its core if its mass is about 80 times higher (the lowest mass limit for a star to form is about 0.05 MSun). |

Figure 07-11a The Jovian Planets |

Figure 07-11b Gushing Moons [view large image] |

Two of the Jovian Planets each owns a moon gushing out water from ocean under the icy surface. They are candidates for future missions to find life in alien seas (Figure 07-11b). |

|

|

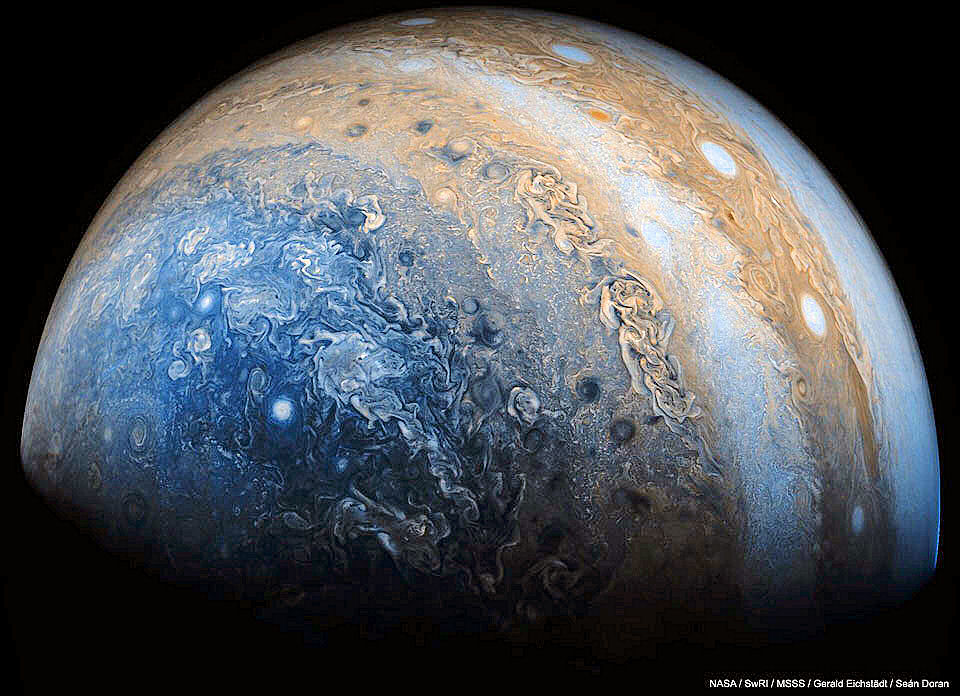

measuring some 25,000 km by 12,000 km, which has been lasted for over three centuries. Jupiter is surrounded by an exceedingly faint system of rings and a family of 16 satellites. Four of the Galilean satellites (discovered by Galileo in 1610) are about the size of the Earth's moon or Mercury. |

Figure 07-12a Jupiter |

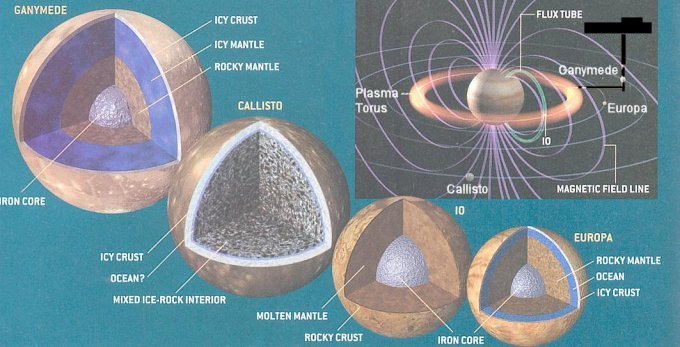

Figure 07-12b The Galilean Moons |

|

|

Figure 07-12c Jupiter, 2017 |

|

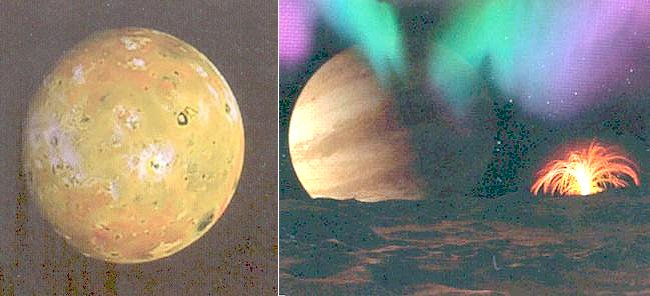

Io is the nearest moon to Jupiter. It is subjected to tremendous tidal force from Jupiter and the three other moons outside. Incessant volcanic activities have turned the materials inside out many times. The surface is pockmarked with craters and lava. The colorful image is produced by sulfur, which takes on various hue at different temperatures (Figure 07-13). Jupiter's magnetic fields interact with Io's ionized gases from volcanic eruptions. It creates a torus of plasma carrying an electric current of five million amperes (Figure 07-12b). The drawing in figure 07-13 shows Io after |

Figure 07-13 Io [view large image] |

sunset with a volcano erupting in the distance. The gasses it has released into the thin atomosphere are glowing in a brilliant auroral display. |

________________________________________

________________________________________

|

The effect of the tidal force on the second nearest moon Europa is not as severe. However, it has melted the water under the ice shell. Europa's icy countenance resembles a cracked eggshell (see Figure 07-14a). Reddish material has oozed out of fractures opened up by Jupiter's gravitational forces. It is thought that the subsurface ocean might harbor life. Although only a theory, this scenario is bolstered by the discovery of life-forms on the Earth's ocean floor that exist in total blackness, sustained entirely by chemical rather solar energy. Bizarre tube worms, crabs, clams and other animals and plants live around warm-water vents in deep-sea midocean rifts, relying on the sulfur and oxygen in the mineral-rich water for the energy required to support them. Drawing on the right depicts an Europa covers with icy crusts, which squeezed up a pingo in the distance. The lower image is an orbital view of Europa. It clearly reveals how the ic-crust surface has been shattered by fractures into iceberglike blocks and plates. Tannish-brown stains around many fractured areas suggest organic material in the water that erupted from below through the cracks. |

Figure 07-14a Europa |

|

A 2011 report on re-analysis of archival data (from the Galileo orbiter) shows that thickness of the ice shell should be about a few kilometers around the chaos terrains (deep crack on the surface) instead of the usual estimate of 20-10 kilometers. It suggests that ice-water interactions and freeze-out give rise to the diverse morphologies and topography of chaos terrains. For example, the terrain in Figure 07-14b is a region of likely active chaos production above a large liquid water in lenticular shape (clearly marked by boundary). The center is sunken below the background terrain (denoted by pale green), indicating the |

Figure 07-14b Chaos Terrains in Europa [view large image] |

presence of subsurface water. Such knowledge is important for selecting future landing site. The drawing on the right is an artist's sagittal view of the landscape. |

|

A 2014 re-analysis of the 1995 - 2003 data from the Galileo spacecraft (Figure 07-14c) reveals that the kilometers thick ice shells on the surface slide around the warmer, more fluid ice underneath. When two blocks of these collide, one would dives downwards or subduct - much like the plate tectonics on Earth. There is a US$2-billions proposal (named Europa Clipper) to build a spacecraft carrying a range of instruments to this moon. So far, NASA would allocate only half of the cost. However, the chance may improve with the help of one congressman (sitting on a powerful spending committee), who is an aficionado of science fictions. |

Figure 07-14c Plate Tectonics [view large image] |

19.

19.

1 in the Solar system.

1 in the Solar system. 8 in some meteorites.

8 in some meteorites. |

|

1032 molecules of H2O. Such plume activity has not been confirmed by subsequent observations despite several attempts. This is not surprising because the ejection of plume is similar to the eruption of volcano on Earth; it requires huge amount of pressure to build up until the fluid can break through the layer of rock or ice (in Europa). Luckily, volcano eruption is not that often in the current epoch of the Earth. |

Figures 07-14d, e; CO2 in Europa [view large image] |

Figure 07-14f Plumes in Europa |

|

|

The electron configuration of the normal carbon atom has 2 electrons in energy level 2S and 2P respectively. By supplying about 2 ev to a carbon atom, the 4 electrons in the 2S and 2P states are rearranged to the SP3 state (Figure 07-14i). The four electrons in the SP3 state form the tetrahedral arrangement (Figure 07-14j) of orbitals (probability distribution of electrons), which can form stable covalent bonds with other atoms. |

Figure 07-14i [view large image] |

Figure 07-14j Tetrahedra |

It is no accident that photosynthesis supplies 6 x (36 ATPs each carrying ~ 0.32 ev + an extra 2 ev) to synthesize 1 glucose molecule.  |

|

the tetrahedral configuration so basic for life. It is more likely that the icy CO2 detected by JWST has an abiotic origin. Its localized presence and occasional plumes can be attributed to tectonic motion of the icy plates (see 2014 report of plate tectonic in Europa). Figure 07-14k shows the analogy of volcanic eruption and lava flow on Earth to plume and CO2 patch (as detected by JWST reported above), the lithosphere is similar to the ice shell, while the asthenosphere can be identified to the ocean under Europa. |

Figure 07-14k Plate Tectonics [view large image] |

|

|

NASA will launch a probe (Europa Clipper) to find out more about Europa on October 10, 2024. It will reach its destination in April 2030. The spacecraft is laden with instruments to gather various kinds of data as shown in Figure 07-14l (see details in "Mission to Europa"). |

Figure 07-14l Europa Clipper [view large image] |

Europa |

It turns out that the project is more than 5 years in its making, and had to surmount a number of crisises (see "NASA okays mission to search for life on Jupiter’s moon Europa"). |

See "Exploring the Composition of Europa with the Upcoming Europa Clipper Mission"

See "Exploring the Composition of Europa with the Upcoming Europa Clipper Mission"

|

In 1996, the Galileo spacecraft revealed that this moon has a magnetic field of its own. Normally, planetary scientists consider such a discovery to be proof of a hot interior with a partially molten iron core. But some researchers have alternately suggested that the field arises in the salty waters of the buried ocean, closer to the surface. In either case, it suggests that Ganymede has participated in a process called tidal heating, in which gravitational forces, associated with Jupiter and its other nearby moons, slightly deform Ganymede and heat up |

Figure 07-15 Ganymede |

its interior. Image on the right shows Ganymede's icy crust. As it shifts and splits apart, water wells up and forms fresh, light-toned swaths of surface. |

|

Callisto is the outermost the Galilean moons and the only one far enough from Jupiter's intense radiation belts to be a possible landing site for Earth explorers unprotected by shielding. It is one of the most heavily cratered object in the solar system (see Figure 07-16). The crater-scarred surface of Callisto appears much as it must have looked four billion years ago, soon after the solar system formed. Callisto's rock is primarily water ice with lunar-like dirt mixed in. At the surface temperature of -145oC, water ice acquires the stiffness of rock, |

Figure 07-16 Callisto [view large image] |

rather than the more plastic characteristics of glaciers on Earth. The drawing on the right shows a remote Jupiter hovering over a cratered landscape on Callisto. |

|

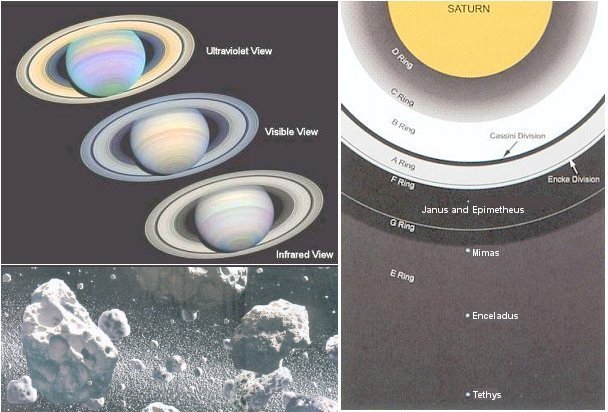

With a density just 0.7 times that of water, it is by far the least dense of the planets. Although it has a slightly longer roatational period than Jupiter, it bulges more markedly at the equator. Saturn's composition and internal structure are believed to be broadly similar to those of Jupiter, but its cloud belts and weather systems are much more muted in appearance than are those of Jupiter. Saturn's most distinctive feature is its system of rings. The rings are composed of billions of individual particles of ice and ice-coated rock, ranging in size from 1 cm to tens of meters (lower left, Figure 07-17a). The rings are extremely thin and flat; they are about 300000 km in diameter, but their thickness is probably less than 1 kilometer and may be only a few hundred meters. Other objects around Saturn are the 18 satellites with diameters ranging from 20 km to Titan's 5150 km (larger than Mercury). The satellites are believed to be composed of mixtures of rock and ice. |

Figure 07-17a Saturn |

|

Titan is unique among planetary satellites in having a substantial atmosphere, composed mainly of nitrogen (90-95%) together with methane (~ 5%) and small quantities of other gases. It has a surface pressure 50% greater than the pressure of the Earth's atmosphere. The temperature at Titan's surface is about -178o C, since the boiling and melting points of methane (CH4) are -162oC and -182.6oC respectively, it is conceivable that this substance can exist simultaneously as a solid, liquid, or gas. Although radar measurements show that at least parts of Titan's surface must be solid, its is possible that significant areas are covered by oceans (or lakes) of liquid methane, ethane (C2H6, BP: -88.2oC, MP: -183oC), or a mixture or both. Figure 07-17b is an artist's view of Titan with Saturn and its rings and moons in the sky. The blue sky envisioned in this drawing has been replaced by orange, smoggy clouds following new discovery in the 1980s. |

Figure 07-17b Saturn & Titan [view large image] |

|

|

Figure 07-17c is an image recorded as the Cassini spacecraft approached its first close flyby of Saturn's smog-shrouded moon on October 26, 2004. Here, red and green colors represent specific infrared wavelengths absorbed by Titan's atmospheric methane while bright and dark surface areas are revealed in a more penetrating infrared band. Ultraviolet data showing the extensive upper atmosphere and haze layers is seen as blue. Sprawling across the 5,000 kilometer wide moon, the bright continent-sized feature known as Xanadu is near picture center, bordered at the left by contrasting dark terrain. On the morning of |

Figure 07-17c Titan |

Figure 07-17d Titan Surface |

January 14, 2005 after being launched from the Cassini spacecraft, the Huygens probe reached the surface of Titan. The pictures in Figure 07-17d were taken as the Huygens probe |

|

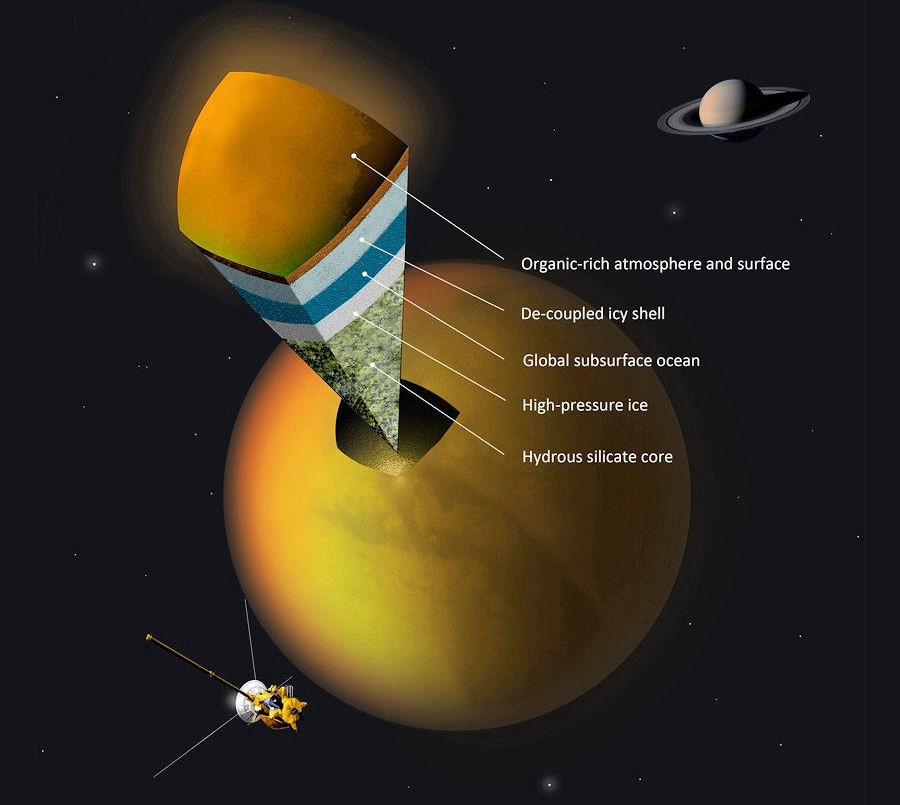

As the Cassini probe flew past Titan more than 80 times, Scientists are now able to infer its internal structure by observing the effect of tidal force on the moon's shape, which can rise and fall by up to 10 meters during each pass. This kind of warpage suggests that Titan's interior is relatively deformable. It is best explained by a model in which an icy shell dozens of kilometers thick floats atop a global ocean. This ocean may lie nor more than 100 km below the moon's surface (Figure 07-17f). Tidal force alone would not keep the ocean in liquid phase, there must be other heating sources such as the decay of radioactive elements or some kind of chemical reactions that dehydrate many of the silicates (such as the hydrated calcium silicate [Ca4(Si6Ol8H2)Ca 4H2O]) there. Impurity such as ammonia can also keep it from freezing. 4H2O]) there. Impurity such as ammonia can also keep it from freezing.

|

Figure 07-17f Underground Ocean [view large image] |

|

|

The average surface temperature on this moon is about -200oC. It is estimated that the depth of the water pool is only tens of meters - easily accessible by explorers. The energy source to keep a liquid ocean deep under the frozen crust may come from radioactive heating and/or tidal heating (by stretching and squeezing a solid object). |

Figure 07-17g Enceladus |

Figure 07-17h |

|

A 2015 re-examination of the Cassini's dust grains collected nine years ago reveals that it consists of silica particles between 4-6 nanometers across. A laboratory simulation can replicate the sample only with a mixture of rock and water at around 90oC. It is then concluded that these particles most likely formed from hydrothermal interactions within Enceladus (see illustration in Figure 07-17i). |

Figure 07-17i Enceladus, 2015 |

The problem now is to explain the energy source heating up the water. The Sun is too far away, Saturn's tidal force is not enough, and radioactive decay has long gone. |

|

Lapetus was first discovered by Giovanni Cassini using a telescope in 1671, he could only see half of the moon. The Cassini spacecraft flyby in 2007 reveals that half of this peculiar moon of Saturn appears as dark as asphalt, the other half, as bright as snow. It is suggested that dark organic-rich gunk, probably from another moon, spatters the side facing forward (as Lapetus always shows the same face toward Saturn). It also shows an equatorial ridge extending across and beyond the dark, leading hemisphere of Lapetus gives the two-toned Saturnian moon a distinct walnut shape (Figure 07-17j). One of the scientific goals is to determine the composition and distribution of surface materials on Lapetus -- particularly the dark, organic-rich material and condensed ices. |

Figure 07-17j Lapetus |

|

|

The new ring extends from approximately 7.7 to 12.4 million km with a vertical thickness of 2.4 million km. It is very close to Phoebe (Figure 07-17l) at a distance of about 13 million km from Saturn. Following the explanation for the origin of the other rings, this ring was formed similarly from material ejected by impacts (with comets for example). Both Phoebe and the new ring revolve in a highly inclined orbit (a characteristic of the outer moons) of 27o and travel in a retrograde manner (moving backward). Thus, it is also suggested that the darker color in Lapetus' leading hemisphere, and the reddish deposits on Hyperion are the results of collisions with the ice and dust in this new ring (albeit these two moons are way outside the ring at about 3.6 and 1.5 million km from Saturn respectively) much like the bugs hitting the windshield. |

Figure 07-17k New Ring |

Figure 07-17l Phoebe [view large image] |

|

|

Figure 07-18 Uranus |

|

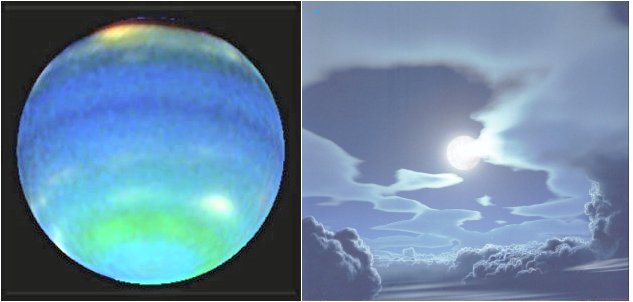

The strength of Neptune's magnetic field at the cloud tops is about twice the surface field strength at the Earth's pole. The magnetic axis is tilted to the rotational axis by an angle of 47o, and, rather than passing through the center, it is offset to one side by about half the radius of the planet. As with Uranus, it suggests that the magnetic field is generated by circulating currents in the ice-rich envelope, not the planet's core. Neptune is surrounded by five faint rings and has eight satellites. Drawing on the right shows thick clouds in the atomosphere of Neptune with Triton glimmer in the light of a tiny, chilly sun. |

Figure 07-19a Neptune |

|

Unique among major planetary satellites, Triton revolves around Neptune in a retrograde direction (opposite to the direction of the planet's rotation). It is gradually spiral in toward the planet, so that, in about a hundred million years' time, it will either collide with Neptune or be torn apart by gravitational tidal forces and scattered around the planet to form a spectacular ring system. |

Figure 07-19b Triton |

|

|

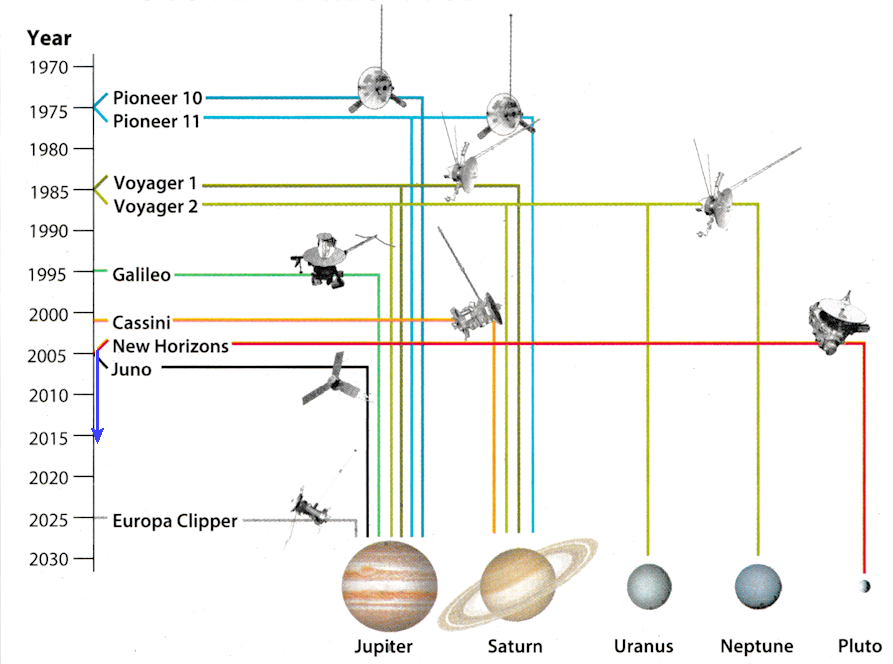

Figure 07-19c NASA Outer Solar System |

Spacecraft Home Page [click icon] |

|

|

Tidal force is a gravitational effect that stretches a body toward another one as shown in Figure 07-19d. In the case of the Jupiter-Europa system, energy of such force is converted to the internal energy of Europa at the expense of the rotational energy of Jupiter (see Figure 07-19e, and LaPlace Rssonance). |

Figure 07-19d Tidal Force |

Figure 07-19e Tidal Energy |

The process is explained in detail by courtesy of ChatGPT below (in Italic) : |