| Home Page | Overview | Site Map | Index | Appendix | Illustration | About | Contact | Update | FAQ |

|

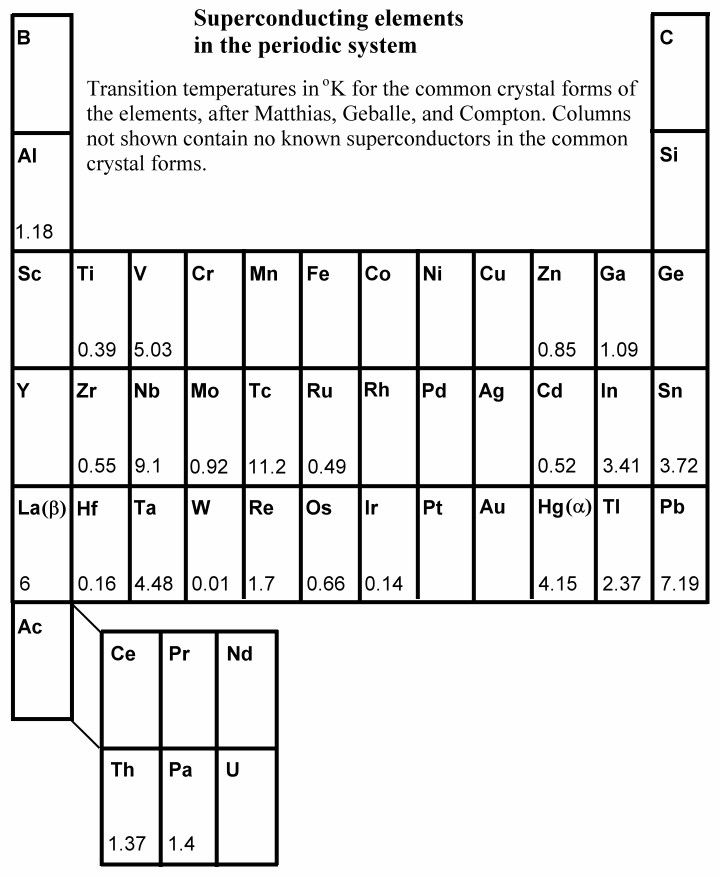

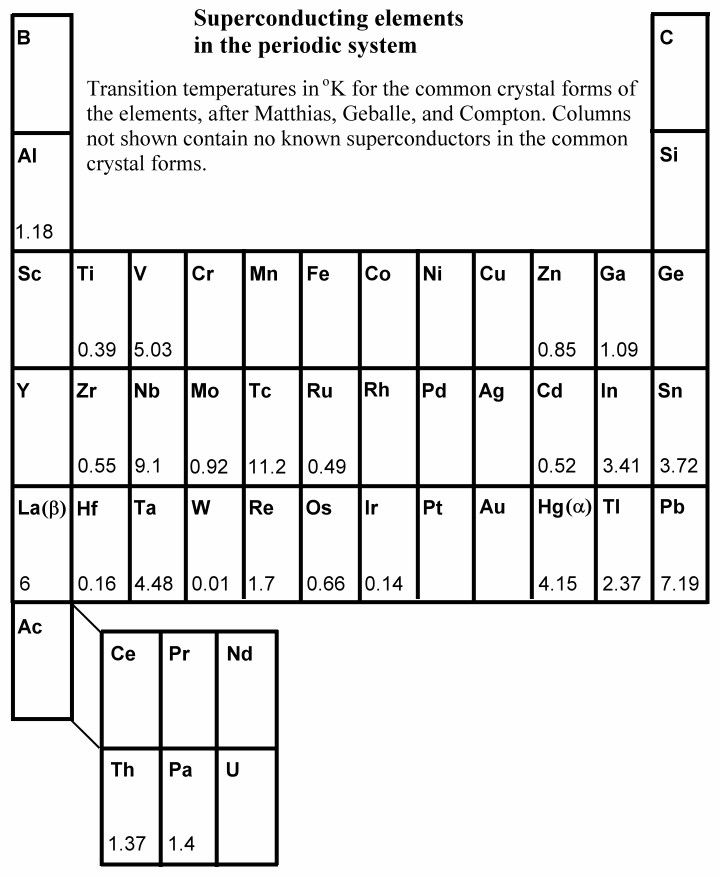

If mercury is cooled below 4.1 K, it loses all electric resistance. This discovery of superconductivity by H. Kammerlingh Onnes in 1911 was followed by the observation of other metals and intermetallic compounds (made of two or more metallic elements) which exhibit zero resistivity below a certain critical temperature Tc. The fact that the resistance is zero has been demonstrated by sustaining currents in superconducting lead rings for many years with no measurable reduction. Table 13-03 shows the elements, which can become superconducting at the indicated critical temperature.

[view large image] |

Table 13-03 Super-conducting Elements |

|

Ceramic materials are expected to be insulators -- certainly not superconductors, but that is just what Georg Bednorz and Alex Muller found when they studied the conductivity of a lanthanum-strontium-copper oxide ceramic in 1986. Its critical temperature of 30 K was the highest, which had been measured to date. Their discovery started a surge of activity which discovered superconducting behavior as high as 125 K. However, these compounds are hard to make and difficult to shape. They pose a multitude of physical challenges to researchers and engineers. |

Figure 13-07 High Temperature Superconductors [view large image] |

Figure 13-07 lists the high temperature (above 4o K) superconductors discovered during the last one hundred years. |

|

|

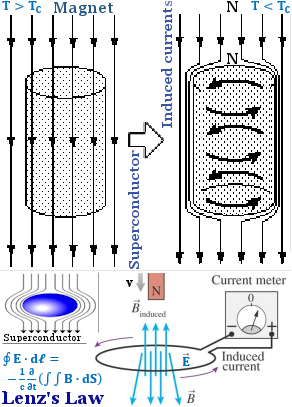

the induced current opposes the initial changing magnetic field. For the case of superconductor (with persistent current) , the induced magnetic field inside the superconductor is exactly equal and opposite in direction to the applied magnetic field, so that they cancel out inside the superconductor. The result is two magnets equal in strength with poles of the same type facing each other. These poles will repel each other, and the force of repulsion is enough to float the magnet (see Figures 13-08a, 13-08b, and "Magnetic Levitation" ). However, the magnet's magnetic field must be below the superconductor's critical magnetic field Hc. If the magnetic field is stronger than Hc it would penetrate the superconductor and extinguish the superconductivity. |

Figure 13-08a Superconductivity Levitation of Magnet (see video) |

Figure 13-08b |

Superconducting electromagnets are used in running the Maglev (Magnetic levitation) trains. |

|

force. This particle was subsequently called the Cooper pair (Figure 13-08c). It can be shown that the most energetically favourable situation for this to occur was when the two electrons had a total spin of zero. Since the Exclusion principle does not apply to particle with integer spin, there is no restriction on the energy state that the Cooper pair can occupy. In particular, at low temperatures thermal agitation is minimal, and all of the Cooper pairs can occupy the lowest possible energy state. Thus no energy exchanges can take place (nothing to give), the normal resistive energy losses are not possible. The Cooper pairs move unimpeded |

Figure 13-08c Cooper Pair [view large image] |

through the superconducting material: it has zero electrical resistance and exhibits superconductivity. The weak attractive force between the electrons in the Cooper pair has its origin in the induced polarization (of the atoms in the lattice, see Figure 13-08c). |

|

|

It was discovered in 2008 that some materials such as the barium iron arsenide (BaFe2As2) behave strangely at low temperature. It starts out in a state of spin-density wave (SDW) in which the charge density (of the conduction electrons) has a sinusoidal modulation out of step from the periodicity of the crystal lattice. This material become super-conductive with doping (substituting arsenic with phosphorus as illustrated in Figure 13-08d) but only up to about 30% beyond which it turns to the normal state of Fermi liquid (free Fermi gas). Another interesting property is displayed by increasing the temperature at 30% doping level, the result is neither a superconductor nor SDW but something called strange metal. This phenomenon cannot be explained by the BCS theory. It seems that all the |

Figure 13-08d Stange Metal [view large image] |

Figure 13-08e Entanglement [view large image] |

electrons in the solid entangled together as a single indivisible whole. It turns out that such complicated system has a counter part in Superstring |