| Home Page | Overview | Site Map | Index | Appendix | Illustration | About | Contact | Update | FAQ |

|

|

At the time of the appearance of the first organisms about 3.8 billion years ago (see Figure 11-04a), there was no free oxygen, as there is now, but rather a "reducing atmosphere" composed of methane, carbon dioxide, ammonia, and hydrogen (see Figure 11-02a). The microorganisms of this period utilized methane or hydrogen rather than oxygen in their metabolism - they are therefore referred to as "anaerobic" (non-oxygen-using). Fermentation is modern example of anaerobic metabolism. This type of metabolism is 30 to 50 times less effective than oxygen-based ("aerobic") metabolism, or respiration. |

Figure 01 Pre-Cambrian Era [view large image] |

Figure 02 Family Tree |

|

|

Up to 700 MYA, life remained fairly primitive, the distinctions between plants and animals were not very clear-cut. For example, the bacteria (monera) show a variety of forms. Some take in chemicals and depend on atmospheric CO2, like plants (autotrophs - from Greek autos = self, trophe = nourishment). Others take in organic material for food, like animals (heterotrophs - from Greek heteros = other). Some autotrophic bacteria, called chemosynthetic, do not need light; they obtain their |

Figure 03 |

Figure 04 Chloroplast [view large image] |

energy from mineral chemical reactions, such as the conversion of sulfur to sulfate or the production of CH4 from CO2 and H2. |

|

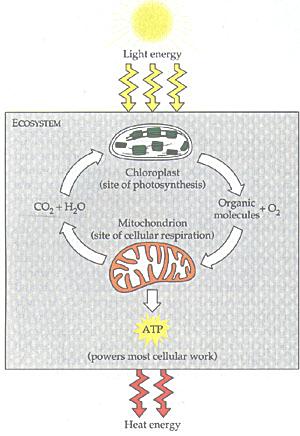

Among the multitude of micro-organisms, two bacteria destined to become the major components for the further development of the living world. The mitochondria (see Figure 03) are the sites of the principal oxidation reaction linked to the assembly of ATP, which supplies energy to most of the organisms today. Their closest relative among present-day bacteria have been identified to be the alpha-proteobacteria. The chloroplasts (see Figure 04) are the agents of photosynthesis in unicellular algae and plants. They store the solar energy in the form of glucose (sugar), which becomes food for the "heterotrophs". Their present-day relative are the cyanobacteria (formerly known as blue-green algae), which is believed to be responsible for the first generation of atmospheric oxygen. As shown in Figure 05a the chloroplasts supply food and oxygen for the heterotropic organims, which in turn produced CO2 for photosynthesis. This ecocycle generates a lot of atmospheric oxygen as shown in Figure 11-02 today. The evolutionary steps for the micro-organisms are shown in Figure 01, which identifies the first organisms to be anaerobic (anoxygenic) autotrophy. |

Figure 05a Ecocycle |

|

(Figure 05b). The researchers think that such a partnership, both biochemical and physical, could tell us more about the processes that led to the eukaryote cell being formed. These living archaea set the stage for the use of molecular and imaging techniques to further elucidate the metabolism of the archaea and the role of ESPs (Eukaryotic Signature Proteins usually found only in eukaryotes) in archaeal cell biology. This, in turn, could guide the direction of future work investigating how eukaryotic cells emerged. |

Figure 05b Asgard Archaea |

They also have to found out how did the archaea acquire a nucleus to become eukaryotic. Updates from further researches : |

|

These proteins are also found in eukaryotic cells, performing different functions. It indicates that these microbes are related to each others although the original purpose has been lost by evolution in billion years. The genes for these proteins actually exist across a variety of microbes and can be traced all the way back to the "Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA)' of all living cells . |

Table 01 Archaea Proteins |

|

Phagocytosis plays an essential role in the older models which have been around since 1967 (aee "Evolutionary Origin of Mitochondria"). Such hypotheses assume that the cells which eventually became eukaryotic were already quite complex, with flexible membranes and internal compartments, before they ever met the bacterium that was to become the mitochondrion. These theories require cells to have developed a way of gobbling up external material, known as phagocytosis, so they could snap up the passing bacterium in a fateful bite (see Figure 05c to compare the difference between the 2 hypotheses). |

Figure 05c [view large image] Theories of Mitochondria Merger |

As shown in the last row of Table 01, the bacteria and eukaryotes have the same kind of membrane. This feature cannot be explained by the phagocytosis models, in which the eukaryote would have its own membrane long before the merger. |

|

Another hypothesis proposes that the first organisms were "heterotrophs"; they derived their food from other organisms or organic matter which they were able to consume. Very soon all the available organic matter was exhausted, and life would have cannibalized itself to extinction, were it not for the appearance of a new type of organisms, capable of manufacturing their own food. They are the very early green plants, which were actually an extremely primitive form of algae, similar to the modern blue-green algae, which assume many forms from one-celled to colonial or filamentous (loose association of cells, Figure 06a). But the generation of oxygen in the atmosphere started a crisis for the anaerobic organisms, which became either extinct or have to adopt to the new environment. Since then most of the organisms acquire their energy from aerobic metabolism. The organisms evolved into animals captured mitochondria for this purpose. While the plant cells incorporated both mitochondria and chloroplasts to survive. They still retain copy of their own DNA within. The DNAs are in a circular form reflecting their more primitive origin (from the bacteria). |

Figure 06a Blue-green Alage |

|

|

Fossil evidences have been accumulated over the years that anoxygenic photosynthesis were used by bacteria 3.4 billion years ago in a sulfuric environment such as the hot spring shown in Figure 06b. It is also known that oxygen-producing form of photosynthesis emerged about one billion years later. The question is : why it takes so long ? |

Figure 06b Sulfur Spring [view large image] |

Figure 06c Photosynthesis Evolution |

|

|

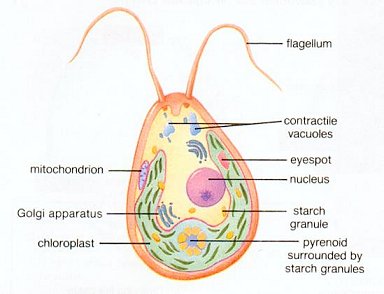

Then evolution took another step toward complexity about 1.5 billion years ago. The bacteria acquired a nucleus and advanced to eukaryotic cells (protista). According to one theory, the ancestral eukaryote is envisioned to be the fruit of an early fusion between an anaerobic, thermophilic, and wall-less bacteria, and a motile eubacterium (bacteria with a rigid cell wall). The product of this union inherited from its progenitors the rudiments of what later became the hallmarks of true eukaryotic cells: the genetic core, histones and actin precursors from the archaeon (thermophile), metabolism and propulsion from the eubacterium. |

Figure 08a Green Algae |

Figure 08b Plant Cell |

Subsequent fusion with mitochondria generated cells ancestral to those of animals and fungi. Acquisition by cyanobacteria in yet another round of fusion launched the photosynthetic protists and plants. |

|

immune system, which destroys biological material not considered "self". But in this case, the salamander cells have either turned off their internal immune system, or the algae have somehow bypassed it. Experiment reveals that the algae gain entry into the embryo when its nervous systems begin to form. The presence of algae in the oviducts of adult female spotted salamanders raises the possibility that symbiotic algae are passed from mother to the offspring's jelly sacs during reproduction. Another intriguing possibility is for the genome of the alga incorporated into the salamander germ cells. |

Figure 09 Salamander Embryos Co-existing with Algae [view large image] |

|

In case of extremely mutual benefit, it becomes endo (within/inside) - symbiotic which is achieved in a very complicated process including passing the trait to later generations. The 2024 experiment "Bacteria implanted in fungi hints at ancient relationships that helped cells evolve" tried to animate the process with only minimal success even by lot of manipulations. |

Figure 10 Symbiotic [view large image] |

The "Human Microbiome" is a living example of symbiotic in all of us. See "Clownfish" for mutualism. |