|

A classical electron moving around a nucleus in a circular orbit has an orbital angular momentum, L=mevr, and a magnetic dipole moment,  = -evr/2, where e, me, v, and r are the electron´s charge, mass, velocity, and radius, respectively. A classical electron of homogeneous mass and charge density rotating about a symmetry axis has an angular momentum, L=(3/5)meR2 = -evr/2, where e, me, v, and r are the electron´s charge, mass, velocity, and radius, respectively. A classical electron of homogeneous mass and charge density rotating about a symmetry axis has an angular momentum, L=(3/5)meR2 , and a magnetic dipole moment, , and a magnetic dipole moment,  = -(3/10)eR2 = -(3/10)eR2 , where R and , where R and  are the electron´s classical radius and rotating frequency, respectively. The classical gyromagnetic ratio of an orbiting or a spinning electron is defined as the ratio are the electron´s classical radius and rotating frequency, respectively. The classical gyromagnetic ratio of an orbiting or a spinning electron is defined as the ratio

|

= -evr/2, where e, me, v, and r are the electron´s charge, mass, velocity, and radius, respectively. A classical electron of homogeneous mass and charge density rotating about a symmetry axis has an angular momentum, L=(3/5)meR2

= -evr/2, where e, me, v, and r are the electron´s charge, mass, velocity, and radius, respectively. A classical electron of homogeneous mass and charge density rotating about a symmetry axis has an angular momentum, L=(3/5)meR2 , and a magnetic dipole moment,

, and a magnetic dipole moment,  = -(3/10)eR2

= -(3/10)eR2 , where R and

, where R and  are the electron´s classical radius and rotating frequency, respectively. The classical gyromagnetic ratio of an orbiting or a spinning electron is defined as the ratio

are the electron´s classical radius and rotating frequency, respectively. The classical gyromagnetic ratio of an orbiting or a spinning electron is defined as the ratio

cl =

cl =  /L= -e/(2me). The minus sign indicates that

/L= -e/(2me). The minus sign indicates that  is in the opposite direction to L (see Figure 07).

is in the opposite direction to L (see Figure 07). /2.

/2.

/2

/2 ), where

), where

a

a

=

=  /dt),

/dt), S = 2

S = 2

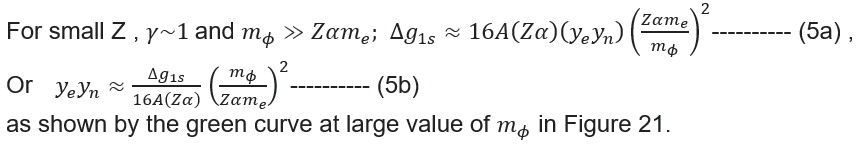

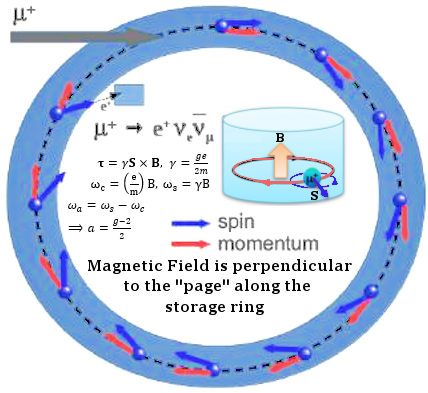

s. However, the detectors lining along the inside of the storage ring will experience cycle of maximum and minimum as the positrons point toward and then away from them with frequency

s. However, the detectors lining along the inside of the storage ring will experience cycle of maximum and minimum as the positrons point toward and then away from them with frequency  )].

)].

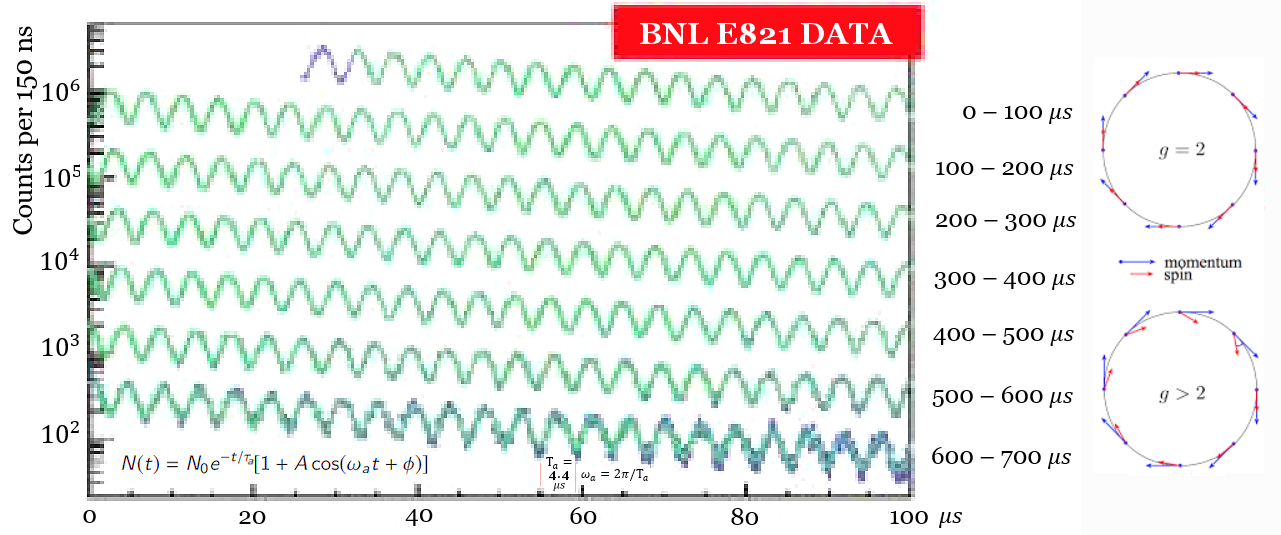

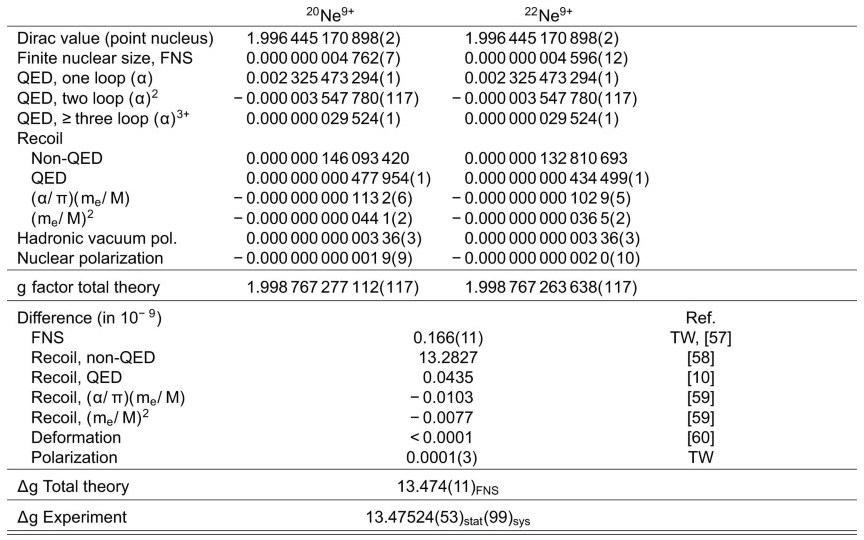

g) between isotopes, many common QED contributions cancel out owing to the identical electron configuration, making it possible to resolve the intricate effects stemming from the nuclear differences.

g) between isotopes, many common QED contributions cancel out owing to the identical electron configuration, making it possible to resolve the intricate effects stemming from the nuclear differences.

L so that the moments pointing at different directions.

L so that the moments pointing at different directions. ] + 0.5 ---------- (1)

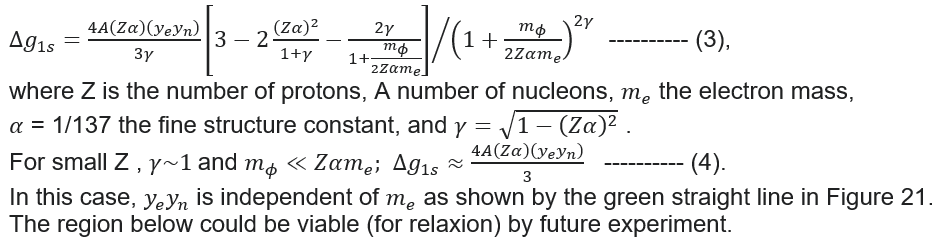

] + 0.5 ---------- (1) by the following formula for the bound electron in 1s state (see more details in "Fifth-force search with the bound-electron g factor") :

by the following formula for the bound electron in 1s state (see more details in "Fifth-force search with the bound-electron g factor") :